Adorno's Constellations (1)

Introduction to the problem of the Universal and the particular

It's not a secret I'm spending much time reading Adorno and analyzing his concepts and ideas. Recently, one of these ideas particularly caught my attention : his thinking in constellations. Let's get back to one of the oldest problem of metaphysics, I'm talking about the Universal and the Particular. Yeah, this is a classic one, especially if, like me, you're studying perception and experience.

I will take here an easy example. Suppose I think about this. You don't know what I am thinking about, right? That's perfectly normal: the concept of "this" is way too broad to be able to guess what I am thinking about. Now suppose I think about this cat. Here the concept cat should put you on tracks, but you are still unable to get what particular cat I am thinking about because the concept of cat is once again too broad to mean anything in particular. Is it a Chartreux? A Siamese? I could go further and add more and more concepts (black, long haired, small ears…) ad infinitum to try to tell you what cat I am thinking about. The truth is I will never be able to express the particularity of this cat for a simple reason: concepts always subsume a certain number of objects and not a single one. In philosophical terms we say that for an infinite intention of a concept, its extension is always strictly superior to one. The intention a of a concept would be its "definition" and the extension every object that falls under this intention. In other words, it means that concept is limited and conceptual thinking can never reach the singular.

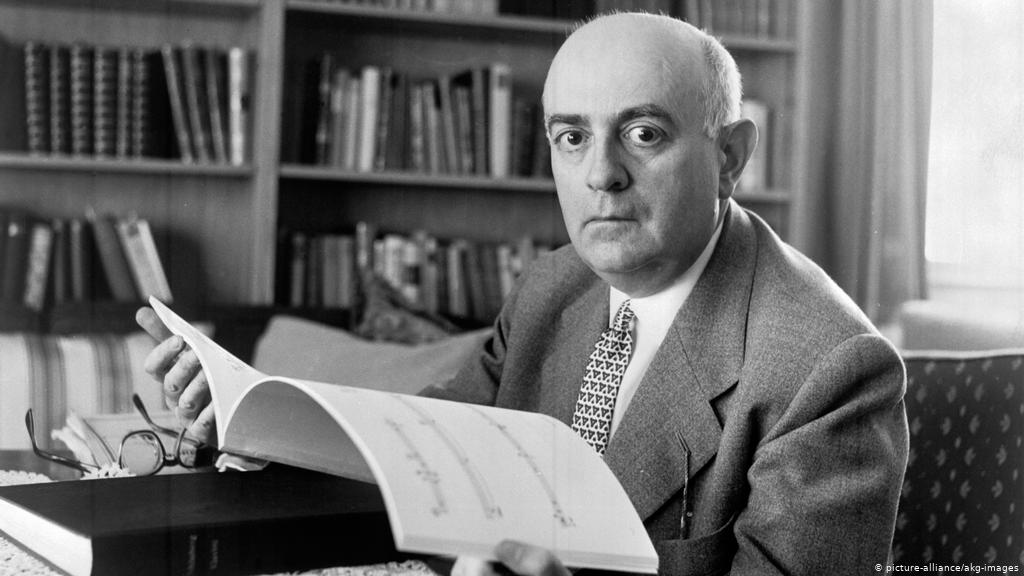

Theodor W. Adorno

Of course, such a problem is gold for a philosopher and once we recognize the limitations of traditional conceptual thinking, we need to build a second concept to overcome the limits of the first one. But this better concept will be as well limited. So, we need another concept to get closer to a complete knowledge of the object.

Adorno is no stranger to this process of striving to extend our concepts but he really owes this to Hegel.

In his Phenomenology, Hegel argues that when the concepts “this”, “here” etc. prove to give us no knowledge of particular things, we must turn to richer concepts (e.g. “dog”, “desk”) that can do so. Moreover, Hegel argues that to grasp a thing as particular we must conceptualize it using a range of these relatively rich concepts. To pick out a particular dog, I must classify it not merely as a dog but also as light brown, friendly, excitable, middle-aged etc. Since no one thing has exactly the same range of characteristics as any other, we can grasp a thing in its uniqueness by using a range of concepts to specify the complete set of characteristics unique to that thing. (Stone, 2008, p. 58)

But Adorno's constellations are very different from Hegel's "ranges of concepts" as Stone puts it. First, Hegel genuinely thought he could reach the uniqueness or identity of an object with a range of concept. This means that a network of concepts would be sufficient to specify all the singularities or characteristics if you prefer this word, and to finally grasp an object in its pure identity, or uniqueness. Then what I wrote in the second paragraph would be completely wrong. But it's not.

There is of course at least something wrong about Hegel's way to reach the singularity of an object: it leads to an utopia. According to him, a network of universals can grasp the singularity of an object, which means, in other words, that singularity is a complex of universals. This implies that we can have an exhaustive knowledge of a particular object if our palette of concept is rich enough. I can't accept this Hegelian solution for many reasons, the first being the impossibility to define the particular as a complex of universals and the second is that I stand firmly by the principle of the second paragraph: for an infinite intention of a concept, its extension is always strictly superior to one, which in this context clearly means that even if we build a giant infinite network of concepts – a big infinite concept – the extension of is concept will be >1. This "super" concept will nevertheless subsume more than one object.

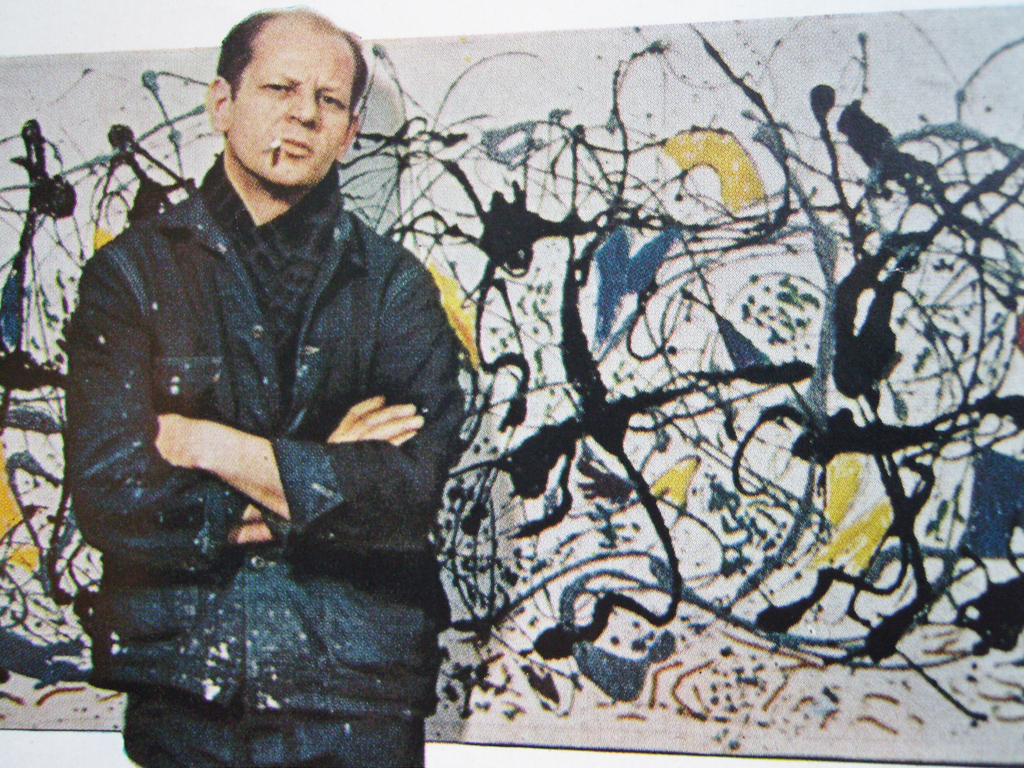

Back to Adorno now. When you read Negative Dialektik, one idea is repeated many times through the book: he talks of the unavoidable insufficiency of ideas and concepts. And this idea comes from another failure of traditional philosophy: the false belief that conceptual thinking and understanding have no limit. Just, as an exercise, try to think and talk about a Jackson Pollock's painting to a friend who has never experienced his art. Do you think that friend will be able to imagine the painting? Do you think you'll be able to grasp and explain the singularity of the painting you're talking about?

Jackson Pollock in front of one of his unfinished work

Adorno's Constellations are designed to answer this typical philosophical problem. His answer could mistakenly pass for close to Hegel's one, but it's not at all. In the next post, I'll try to illuminate the concept of constellation and prove his importance in nowadays philosophical discourse.

Bibliography

Stone, A., Adorno and Logic, in Cook, D. (Ed.). 2008. Theodor Adorno. Taylor and Francis.

Find Paul Dablemont on mastodon | Get Philosophical Annexes in your inbox | © 2024 Paul Dablemont. All rights reserved.